Popular Posts

-

The moon petals the sea. Rose petals the sea. Stone sea. Stone petals. Rose petals of stone. Stone rising before me. Sea moves. How moves...

-

As Antony Gormley's One and Other 100 days project for the fourth (empty) plinth in Trafalgar Square neared its conclusion I found mys...

-

extract from the poem Koi by John Burnside All afternoon we've wandered from the pool to alpine beds and roses ...

-

Hello everyone who follows David King (My Father). On behalf of the family this post is to let you know that Dad sadly passed away, peacefu...

-

It all depends, you see, how you go about it. And that I cannot tell you, for that will be dictated by you and by you knowing your friends...

Thursday 31 December 2009

Not a Haiku : Not a New Year Resolution,

What comes from heaven changes earth.

Bodies wrapped in shrouds of snow

a white tsunami

with its human load

Wednesday 30 December 2009

The New Year : Symbols and Traditions

Actually, its symbols and traditions are legion, so what follows is a quick look at a few that I find particularly appealing.

The Tray of Togetherness is one that seems to recommend itself at this moment in time. (Recent news items would suggest that it is particularly need at this hour.) It is Chinese (you might well think me to be on some sort of Chinese kick, but it has just happen ed this way) and consists of a tray with eight compartments, each one of which is filled with a special item of food. The trays are offered to guests who visit during the New Year (Geng Yin) festivities. For the Chinese, our year of 2010 (their year of the tiger) begins on he 14th of February.

Janus The two-faced Roman God had January 1st dedicated to him by the Romans, as with his two faces he could simultaneously look back into the past and on into the future. He was also known as The God of Beginnings and Endings.

Candles Very familiar symbols, almost omnipresent at Christmas and The New Year, symbolising the spreading of light and warmth, but also it was understood that the smoke would rise into heaven, thereby ensuring that God would answer prayers.

The Yule Log Symbolises the return of the light to conquer darkness. It should be burnt for one whole night, then smoulder for twelve days (one day for each month of the year) and then extinguished imperially. Nowhere can I find any guidance as to what would constitute an imperial extinguishing!

Plum Blossom. Chinese again! Symbolising courage and hope. The blossom bursts forth at the end of winter on what appear to be lifeless branches.

First Footing As a boy I always associated the new year with Scotland. We had Christmas as our big occasion and they had the New Year - and what was more, they knew what to do with it, unlike us. My dad was stationed at Morpeth, Northumberland, during the war and made friends with a Scottish family. At times he managed to spend New Year (Hogmanay - Hog-mah-nay - with them, and would tell me of their celebrations). First Footing involved visiting friends and neighbours carrying a lump of coal for their fire or - intriguing this, I always thought - some shortbread, in return for the traditional hospitality they would show to the visitor. It was considered lucky if the first visitor over your threshold was tall and dark.

Auld Lang Syne Really belongs in the above paragraph. An evergreen part of the Scottish Celebrations. Literal translation: Old Long Since. It has been dubbed the most popular song whose lyrics are known by nobody. Not popularised by Robbie Burns as most folk believe, but by the band leader Guy Lombardo.

I finish with three from abroad that have particularly endeared themselves to me.

Spain The tradition is to eat twelve grapes at midnight, one for each month of the new year - don't know why that specially appeals, but it does.

The Netherlands People here, burn their Christmas trees and let off fireworks - it's the burning of the trees that appeals.

Japan Oshogatsu Their New Year parties (Bonenkai) are in fact forget-the-old-year-parties. From a family dimension we have had a particularly forgettable year, so this one seems the one for us for this year at least.

A Very Happy New Year to You All

Saturday 26 December 2009

Poems of the Masters:

A Christmas-post-Christmas enthuse.

Let me first risk putting you off this book and then, assuming that the unintended has come to pass, let me try to reverse that unfortunate consequence. Here we go then, one short sentence should do it: It is an anthology of Classical Chinese poetry, some of which dates from before the early eighth century. There you are, then. What did that do for you? Have I lost you? Hopefully, not too many of you, but both eighth century and Classical can be slightly off-putting, as can the word anthology. Anthologies are for some anathemas, and for most not books to make the pulses race. So now, to reassure you, let me suggest that this book and these poems have more than enough on the plus side to outweigh those disadvantages. First up is the fact that the T'ang and Sung dynasties are regarded by the Chinese as their Golden Age of Poetry, something akin to our own Elizabethan age, when after a long period of development, the language gelled with new concepts in writing to produce a richness never seen before - or, some would argue, since. Indeed, it was Ezra Pound's discovery of these ancient verses that set him on the road to his invention of Imagism.

This anthology was first compiled (in Chinese) towards the end of the eleventh century (though this is the first - and still the only - complete English translation), and was the basis of of all Chinese Classical poetry and Education from that time until it was replaced by political propaganda when China made its more recent foray into Communism. The book's English translator, an American who goes under the pen name of Red Pine, has written an insightful introduction. The Chinese ideogram for the word poetry, he tells us, actually means language of the heart. That is to say, it is more an expression of the poet's internal landscape than an attempt to convey the external or physical world.

There are 475 pages to this book, 224 poems in all, each set out on facing pages, the Chinese original on the left and the English translation to the right. Additionally, at the bottom of the pages, Red Pine includes notes on the poem and the poet. But in all that there are only four distinct poetic structures, a fact easy to appreciate as the book is divided into four parts, each part being dedicated to one of the four forms. There are:-

39 poems of four lines with five characters per line,

45 eight-line poems with five characters per line,

94 poems of four lines with seven characters per line,

and 46 eight-line poems with seven characters per line.

Obviously they will not work out like that in English. The Chinese characters do not correspond to a fixed number of English words or syllables, but the originals are there to give an idea of their Chinese forms. Something of this can be absorbed even by those who do not read Chinese.

By structure, however, more is meant than simply the line or character count. Each poem-type follows complex rules as to rhyme scheme, tonal pattern and parallelism. Such considerations will not interest every English reader of course, nor need they, for there is much to savour without having to wrestle with such complexities.

The first poem in the book, Spring Dawn, is one of the great favourites with the Chinese people, and it is not difficult to see why. It is seventh century and by Meng Hao-Jan. The form is 4 lines of 5 characters per line - known as wu-jue.

Sleeping in spring oblivious of dawn

everywhere I hear birds

after the wind and rain last night

I wonder how many petals fell

An interesting point here is that in the original Chinese version no pronouns were used. Red Pine has inserted them: I hear... and I wonder... but the poet Meng Hao-Jan avoided them. It is as though he wanted to leave his readers with the feeling that the phenomena being described were witnessed by some impersonal being or manifestation - perhaps of nature itself. As such it would be a stunning example of the power of Chinese poetry to express abstract ideas in concrete images.

In his notes, Red Pine also highlights the wonderful piece of characterisation that is going on here: the poet being able to conceive the possibility of lying there wondering about the scene outside - without at all feeling any compulsion to get up and go outside to see at first hand.

One of the downsides to anthologies, I always think - certainly of Western poetry - lies in the fact that you miss the threads of meaning, the nuances of influence and concern, the development of ideas that poems in a one-poet collection give to the works around them. Reading poems in isolation is not at all the same as reading them as part of the collection, as part of that in which they were conceived. Now that which follows may stem from a misunderstanding on my part, but it does seem to me that these considerations do not apply to the same degree when we come to Chinese poetry. Here the rules governing their composition and limiting the development of each poem are so strict that continuities bind them together in an anthology almost as tightly as in our culture the poems in a one-poet collection are bound. In both form and content there is much continuity. Indeed, there is something of a family feeling.

Nowhere is this more the case than in the two eight-line forms. Here the rules have the sort of force that is normally reserved for laws. You infringe them at your peril. They are numerous, extreme and inflexible. They extend beyond the verbal into visual and musical elements. For example, they lay down that the third and fourth lines must be mirror images of each other, as must the fifth and sixth. And by "mirror images" we mean that nouns must face nouns (you need to look at the Chinese versions to see how this might work out), verbs must face verbs, adjectives, adjectives and adverbs, adverbs, and so on. But the rules are more extensive even than that: they say that numbers (if used) must face numbers, colours, colours etc.

You would think, maybe, that poets would be using their ingenuity to circumvent these rules - or maybe just ignoring them or avoiding those verse-forms altogether. Far from it. Many of the best poets, Tu Fu for example, have taken them even further, constructing the eight-line versions from four matched pairs - and in doing so increasing exponentially the problems facing translators!

For me one of the joys of this book has been the notes which accompany each double page spread. Here is an example:

The Chungnan Mountains

by Wang Wei

Taiyi isn't far from the Heart of Heaven

its ridges extend to the edge of the sea

white clouds form before your eyes

blue vapours vanish in plain sight

around its peaks the whole realm turns

in every valley the light looks different

in need of a place to spend the night

I yell to a woodcutter across the stream

The notes explain that Wang Wei (701 - 761) was an influential official who rose to be deputy prime minister, but much preferred to be at home in his beloved mountains and spent as much time there as he did at court. Taiyi (The Great One) was another name for the Tao. It was also another name for The Chungnan Mountains and for their highest peak. The Heart of Heaven refers to the Taoist paradise as well as to the Son of Heaven's residence. White clouds represent a life of detachment and blue vapours worldly aspiration. The Chinese at one time laid out the empire into twenty-eight realms corresponding to the constellations of the Chinese Zodiac, all radiating from these mountains. Upon meeting a woodcutter, a herb gatherer or a hermit in the mountains of China, even a stranger soon feels at home.

One of the big differences between Chinese and Western poetry lies in the fact that the former does not describe an event (as Western poetry often does), but a situation. This is sensed, I believe, at the time of one's first encounter with the Chinese art-form - as, for example, in the case of the following poem. Red Pine gives the narrative background to the work, but the poem itself represents a moment... I was going to say a moment in time, but in fact time, in the sense of time passing, does not exist. The reason for this is quite simple:

Chinese verbs have no tense - though Red Pine does introduce tense in some of his translations. Nevertheless, if we are to believe those versed in both languages, the original feel remains.. One of Ezra Pound's most perceptive pronouncements was that images can create insights in a second. It was the mainspring of his inspiration and, more than any other fact, led him to the creation of Imagism.

Here then is first one of the four-line verse-forms:

The Peach Blossoms of Chingchuan Hermitage

by Hsieh Fang-Te (1226 - 1289)

In Peach Blossom Valley they escaped the Ch'in

peach blossom red means spring is here again

don't let flying petals fall into the stream

some fishermen I fear might try to find their source

Red Pine explains that when the Mongols brought the Southern Sung dynasty to an end Hsieh had formed an army of resistance, but he was defeated, captured and imprisoned. He starved himself rather than serve his new masters. Here he visits a hermitage and describes how a fisherman followed peach blossoms that were drifting down a stream until he reached their source in a cleft in the rocks. Squeezing through the crevice, he came out in an idyllic valley, where he met people whose ancestors had come there several hundred years earlier to escape the brutal rule of the Ch'in dynasty (221 - 217 B.C.). After returning to tell others of his discovery, the fisherman was unable to relocate the valley, as the refugees had obscured the trail and the crevice. Hsieh uses the Ch'in here to represent the Yuan (1280 - 1368), from whose encroaching dominion he hoped to find refuge.

And now another eight-liner:-

Commiserating with Gentleman-in-Waiting Wang on Tungting Lake

By Chang Wei (720 - 770)

Through Tungting Lake in the middle of fall

the waters of the Hsiao and Hsiang flow north

but home is a thousand-mile dream away

and a guest greets dawn with sorrow

there's no need to open a book

far better to visit an inn

Ch'ang-an and Loyang are full of old friends

but when will we join them again

The author was a minor official who had been rusticated to Changsha, in the province south of the Tungting Lake. The title Gentleman -in-Waiting, Red Pine explains, was an honorary epithet for someone who had been sponsored as an official but had no formal position. He was thus exempt from the civil service exam (< i>No need to open a book) Chang watches the waters of the two rivers flow north through the lake, into The Yangtze, and towards Loyang, while he and his friend wait to be recalled to the capital.

Tuesday 22 December 2009

Party Time : amuse - or lose - your friends this XMAS

It all depends, you see, how you go about it. And that I cannot tell you, for that will be dictated by you and by you knowing your friends as well as you do. Get me? Okay, in essence this is what you do: you give them all a sheet of paper and some pens, crayons, paints, body fluids - whatever turns you (and them) on - and you ask them to draw or paint a picture of Father Christmas to the very best of their ability. Not artistic ability, mind. Not drawing ability, no that is not what we are drawing on at all. They just need to summon up to the very best of their ability an image of Father Christmas in all his detailed glory and get as much of that as they can down on the paper.

Then you n eed to mark it - or they mark their own or each others or whatever. For which there is a marking key, viz:- One point is awarded for each of the following details included in the drawing:

1. Head present

2. Legs present

3. Arms present

4. trunk present

5. The length of the trunk is greater than its breadth

6. Shoulders are indicated

7. Both arms and legs are attached to the trunk

8. As above, all attached at the correct points.

9. N eck present

10 Neck continuous with head and/or trunk

11 Eyes present

12 Nose present

13 Mouth present

14 Nose and mouth in 2 dimensions and 2 lips indicated

15 Nostrils indicated

16 Hair shown (For hair, you might decide to read "whiskers"!

17 The hair is non-transparent over more than the circumference of the head.

18 Clothing present

19 Two items of clothing non-transparent

20 Both sleeves and both troser legs shown non-transparently.

21 4 or more items of clothing definitely indicated.

22 Costume complete - no inconsistencies

23 Fingers shown

24 Correct number of fingers shown

25 Fingers shown in 2 dimensions - ie their length greater than their breadth and at an angle of less than 180

26 Opposition of thumb shown

27 Hand shown distinct from fingers and arms

28 Arm joint shown - elbow and/or shoulder

29 Leg joint shown - knee and/or hip

30 Head in proportion

31 Arms in proportion

32 Legs in proportion

33 Feet in proportion

34 Both arms and legs in 2 dimensions

35 Heel shown

36 The lines are firm and do not overlap at junctions (unlike the drawin gs of many famous artists!)

37 Firm lines with correct joining

38 The head's outline is "shaped" - i.e. is not just shown as a circle.

39 Trunk outline ditto

40 There is no narrowing of the limbs at their jun ctions with the body

41 The features are symmetrical and in their correct positions

42 Ears present

43 Ears correctly positioned and proportioned

44 Eyebrows and eye lashes shown

45 Pupil(sL of eye(s) shown

46 The length of the eye(s) greater than the height

47 Eye glance directed to front in profile

48 Chin and forehead both shown

49 Projection of chin shown

50 Profile has less than two errors

51 Correct profile

You have given your friend(s) The Goodenough Draw a Man Test. This used to be administered to young children (3 - 10 years) to establish their mental age and/or I.Q. (Oh, God, it's not still being used is it? Tell me it's not!) It's up to you whether or not you tell them that they have just betrayed their mental age/ I.Q . If you go that far, it's up to you whether you also impart the information that the test is incapable of producing a mental age greater than 15 3/4 years.

It might depend on whether or not you were planning a cull of your friends this year or wanted to see which of them were the best sports or... well, you know what you're doing! To proceed: You give everyone a base age of 3. You then add 1/4 year for each point scored. Thus 9 points would equal 3 + 9/4 = 5 1/4 years.

Saturday 19 December 2009

Here Be Dragons

we called a twittern. Half its length it ran

between the big house, Glebelands, and our six-

foot fence, then turned its back on us, dog-legged

away, but kept its tight embrace on all

the mysteries the shrubs and railings hid.

In there were demons, types unspecified.

Lights blazed at night and blinds were drawn, but no

one came or went, the gate was always locked.

"Beware the dog!" it said. There was no dog,

the whole gang knew, just dragons in the grounds.

The dog-leg was the only doggie thing

in sight. And standing in its corner, tight

against our fence from where its flickering light

fell softly on the path in both directions

for a yard or two at least, among blown

leaves and litter, my own lamp, my gas light,

lit each evening by an old man with a

ladder. As punctual as sun and moon,

he'd come at dusk and I would wait - but with

this prayer: "Please God, this one night, make the lamp

man late - and very late!" (His coming was

my time for bed - at least when winter came.)

The twittern took you to another road:

Love Lane. More mystery, more need to know

of things the adults talked about in code.

Love Lane had one enormous pearl of such great

interest that all else paled beside it:

I loved the evil-smelling smoke and fumes

discharged by its satanic Gas Works - all

the more because the grown-ups hated them.

That black hulk cast its shadow far and wide - and

well within its ambit lived my friend Paul Death.

(De' ath, it should have been, to be precise -

though no one ever had been that precise.

Death, he was meant to be, and death he was.)

My house was number one. Big deal? Had that

been it, the whole of it, there would have been

few bragging rights, but there was more, much more:

the road was Queen Anne's Gardens - which, the way

I'd say it, had a touch of gravitas.

The inference was meant: "Beat that!" Few could,

of course. Now add my regal-sounding name,

my David, Alexander, King... how would

they not have been impressed? The house that thought

itself a palace looked straight down Glebe Path

towards a green, Church Road, the Town Hall and

the fire brigade (these last two out of sight).

Firemen were housed in our road and Glebe Path.

Heroes we had as neighbours! Comics too. Star

turns, for we would see them, jackets flapping,

half on, half streaming out behind, caught, twisted

and misshapen like so many broken

wings on injured birds, their owners fluttering,

in half-flight, hopping, stumbling from our sight

the moment that the bells went down, their wives in

close pursuit, arms stretched towards them, helmets in

their hands, but losing ground. We'd laugh and cheer.

The Green possessed an air raid shelter, built

of brick, above ground, famed residence

of our own Parish Belle. She had a corner

dedicated to her bits and pieces.

The grown-ups that we knew all spoke of her

as "rank". The "rank", it seemed was "higher" than

the gas works boasted. Some confusion. Some

thought her a princess or a queen. Whatever,

no one would bother her. She came and went.

Just once she had a sack of "rank" manure

as a bed. Too much! She'd have to go - she

or it. At which the penny dropped for us.

In Church Road, close to where it joined Glebe Path,

a corner shop, Sunshine and Bombs, the name

a soubriquet, of course, conferred upon it

and the lady owner, by my father

when she'd told him how she hated sunshine

and how she much preferred the German bombs!

A short way further on was where a plane

machine-gunned Paul and I as we walked home

from school. Or maybe not. A German plane

and very low - we saw the crosses on

its wings. And damaged too: thin trails of smoke,

and both the engines stuttering. And that,

perhaps, is what we heard, though at the time

we had no doubts - and dropped down flat and lay

there in the gutter 'till its sound had gone.

Much further on, a bend, another dog-leg,

knobby at the knee this one, the knobbies

being three: my school, The Parish Church - where

I would soon become an altar boy - and,

most protuberant of all, The Star, a pub

whose name alas the locals lent the school.

Beyond this point I did not venture - ever.

Had I done so, Merton Abbey might have

hove in view, as might Lord Nelson's home, where

waited patiently - or not - his Josephine.

First day at school, the teacher telling us

to wrap up - scarves, gloves, coats and hats, the lot.

Home time. What else could it have been? I went.

My mother hoovering. Dismay that I

had walked so far and crossed a busy road

alone. The head all smiles and pats on back.

Next time to wear my thinking cap. Bafflement.

And then again, by socks that needed to

be pulled. Why do the grown-ups use such codes?

More dragons roamed the graveyard round the church.

One grave, its stone lid lifted quite enough

for braver souls to put their hands inside,

was known by all to be their lair.

My father said the only dragon was

the priest. Officiating at the war

memorial, he'd walked away, left all

the people and their planned observance high

and dry at its most solemn point - and all

because he had detected in the crowd

a body of dissenters. Methodists!

A memory of adult stuff - my first.

Thursday 17 December 2009

OK, I'm going soon - and when I do...

About six months ago a young friend of ours died of cancer, having previously made it known that when the time came he would like to have his ashes fired into space in a rocket. (By space I do not think he meant deep inter-stellar space, just up there.)

At the funeral directors' his parents were shown two albums, one of the various ways in which the deceased can be remembered - and one of the many methods of disposing of the ashes. And yes, being shot up into space in a rocket was one of them. (I actually heard the other day of a chap who thought he would like to become an egg-timer.) One option is to be made into a diamond. The ashes are subjected to great heat and pressure, replicating (as near as) the natural process. His parents are still waiting for it to be arranged - with air traffic control, perhaps. It has to be done at the coast, it seems, the rocket fired over the sea.

We happened to be talking about these things (as you do!) when, low and behold, in the readers' letters of Saturday's Guardian (I think in connection with Seamus Heaney's campaign to have Ted Hughes remembered in Poet's Corner in Westminster Abbey - it didn't seem to relate to any other article) six cartoon-type drawings with captions under the following heading:

In the event of my death I would like to be memorialised with (tick one box):

The six boxes were:

1 Small plaque

2 Heroic statue

3 Spooky tree

4 Colossal ziggurat

5 Haunted fruit machine (why haunted... anyone?)

6 Network of secret tunnels.

Some of you will know from a past post or two of my childhood obsession with secret tunnels, so I was rather tempted by that, but then I thought, well if they were really secret no one would know where I was or be able to visit me. So, no... and none of the others appeal in the slightest. So what to do? - and time is running out, no?

I have this obsession that funerals, burials and cremations, the scattering - or not - of the ashes, all that is for the mourners. It is all a part of the grieving process. I do not believe that the about-to-be-deceased should stick his - or her - nose in. But, they say, it's part of the grieving process for the family to feel that they are carrying out the deceased's wishes.

No one's pressing me, you understand. I've not been given a deadline... thing is, I've just had this one moment of inspiration: an artist to be commissioned to paint a landscape, an artist who works with a thick impasto of paint. My ashes to be mixed in with the paint. My version of scattering them across The South Downs... even better, a seascape!

Still, I'd be grateful for any other bright ideas, just in case the guy with the scythe says all of a sudden, "Hey, fella' me lad, it's make yer mind up time!"

Sunday 13 December 2009

Trees like us.

(ancient books with leather bindings, in the main),

the car lights seem to hesitate on each

erect or leaning London plane -

the odd one leaning, reeling maybe, from the weight

of all that learning locked inside.

The spines, so smudged with soot

and halogen, betray no titles. Patched

and scaly sages, they remind us

of the boundaries that nature draws

round vision, they and those

frail sapling paperbacks,

who here and there have found a home

in what were narrow spaces, they

and the odd weighty tome

that squeezed in horizontally,

too tall to stand upright.

Behind them, sealed in pathless darkness,

a great wood stretches to infinity,

but these sad London planes,

each one an interface between the unknown

and ourselves, our world

and that opacity - the border guards,

as we might like to think of them,

denying or permitting access to

that darkling world of learning

to their rear. Could we but take one down

and open it like those at home,

a world might open in its turn:

horizons we could not have guessed,

bright looms of morning light.

They draw up wisdom from the soil,

absorb it from the air.

They store it in the grain.

and feed it to the millipedes

that live beneath the bark.

The spiders spin it in their webs;

you hear it in the groans

and creaks, the timbre of each voice. It speaks

a thousand languages, and scribes the wood

with arcane signs like charged Rosetta Stones.

If we could prise the boards apart

and cut the uncut leaves,

achieve for them what still eludes...

Unqualified transparency - would not that form

the perfect attribute for any London plane?

A tree entirely open to the gaze,

complete with soundtrack, growth and rending,

a universe once worlds away, at home in ours,

a world with all its life and lives intact,

decay and growth and mini beasts;

the struggle for survival and the end in death,

tides that rise, turn, fall and vanish out of sight,

the laughter and the tears of life that wills to live.

Wednesday 9 December 2009

Catching my Eye

Now here is the key - just in case you need to know some day!

1: A good target.

2: Occupant, nervous and afraid.

3. Nothing worth stealing.

4. This house is alarmed.

5. Vulnerable female: easily conned.

6. Too risky.

7. Wealthy owner.

8. Has already been robbed.

Further comment is, I think, superfluous.

Except... gelling with so much talk of climate change and the parlous condition of the earth, it set my mind fancifully thinking what if aliens, robbers say, the extraterrestrial equivalent of Viking raiders, were to chance upon earth, recce it and leave the fruits of their reconnaissance in orbit. What would their signs say? Here, I have managed just two suggestions:-

Any more from any more?

Then there was the Andy Warhol Red Portrait affair. You may have seen this, too. Andy Warhol made ten identical red self-portraits. Excuse me while I rephrase that: there are ten identical red silk-screen portraits of Andy Warhol. David Mearns, a Sussex business man has one of them. It was to have been offered to the Tate, but has now been withdrawn. There exists a New York Foundation that pronounces on the authenticity or otherwise of works by, or said to be by, Andy Warhol. It offered to authenticate the work. The offer was turned down flat by David Mearns, who has accused it of making such offers in the past with the sole intention of stamping Denied on the back so as to destroy the value of the silk screen prints. From time to time the Foundations sells works that it owns, and so has a vested interest in the scarcity value of its own works.

And so the battle was joined: is the red portrait a fake or a valuable Warhol? The case for its authenticity is its provenance. Andy Warhol gave a photograph of himself to a friend. It was an automatic image produced by a bog-standard photo-booth. The friend passed it on to an outside firm. They produced the silk screens from it - and presumably ran off the prints. The finished prints were looked at and approved by Andy Warhol... and that's the case for the defence? Yes, my lord, there the case rests. What thinkest thou, O juror?

Good to see a painting taking the top Turner prize. Good, too, to see that beauty is the new ugly and to know that paint is okay again. I would not wish to exclude ugly, you understand, but it takes all sorts to make a world - even a fragile, fleeting world that is tied to a moment , a situation or an environment.

Richard Wright was asked - only natural, I suppose - if he had any plans for the prize money. His reply was that, like everyone else, he has bills. Since he has covered a rather large wall with the gold leaf that is destined to painted over at the exhibition's close, I just wonder if his bills really are like every one else's.

Sunday 6 December 2009

A Glimpse of Darkness

became a psychic force. A boy, untroubled still

by any hormone rush,

I could not, not for him, not for the gifts he gave,

nor yet for threats of greater darkness,

embrace his.

His was a world of great malevolence;

unspeakable diseases, hell-hags, ogresses

and nightmares. But the evil was

the devil was all women - and even as he'd speak

they would be plotting for my downfall.

He had seen it all,

had witnessed it in war-torn Italy:

the blistered flesh of conscripts following the path

of natural desire.

He too was victim, brought his own light: introduced

me to great music, bought my first

L.P.. Beethoven.

The Appassionata. Images there are,

agendas, propositions that sit awkwardly

with art - and even art

not fully understood, draws boundaries.

The music flooded me

and set me free.

Thursday 3 December 2009

Here's one I made earlier

In the very early 80's the government, in its infinite wisdom, decreed that every school in the land should receive a computer. Ours duly arrived, a pristine, cutting-edge BBC computer produced by Acorn to a BBC-determined, government backed specification as part of a much vaunted literacy project. Along with all the others in the land, our (Special Needs)pupils were to be whisked into the computer age. The aim was not just literacy, but computer literacy as well. All this with one computer between 130 children. And it might have happened - up to a point - had they thought to include some software in their generous package. Alas, suitable software was not available. It was in the pipeline - a rather long pipeline as it turned out. A few of us decided that we would learn a computer language and have a shot at producing some software for ourselves. (After all, computer languages couldn't be harder to learn than French or Spanish - could they?) Whatever. A combination of in-service training courses, self-help from books etc and weekend courses run by companies trying to get in on a government hand-out, resulted in a few of us becoming half-way proficient with Basic - BBC Basic to be exact.

One of the exercises I gave myself in an attempt to get to grips with graphics was to write a program that would produce Mondrians. It was primed with the few basic rules that Piet Mondrian had at one point set for himself (periodically he would modify his ules to extend what was allowed)and would either choose random values within those rules or could be controlled by the user. The rather sad, faded specimen that emerged from under that pile of magazines is probably the only original extant King-Mondrian. As a result of our efforts, we did manage to produce some programs with which to introduce our youngsters to the delights of computing whilst actually teaching them something at the same time. Very amateur they were, of course. Laughable by the standards that even very young children would come to expect in just a year or two's time, but it was - we kidded ourselves - a start. And then one wet playtime a teacher thought it a good idea to set up the computer with one of the - not very educational - games which by then had come our way. By mistake she loaded in the Mondrian. Surprisingly, they took to it, and even became very competitive in comparing their efforts. Even so, it took a new lease of life after it had been explained to them what the pattern things were. They immediately saw themselves as counterfeiters and enjoyed the feelings of doing something that could be seen as both adult and illegal. In no time at all there were Mondrians hanging on all the school walls.

Below, in fairness to Mondrian, I give you one of his.

And some of his thoughts:

Everything is composed by relation and reciprocity. Colour exists only through another colour, dimension is defined by another dimension, there is no position except in opposition to another position. Form and colour have found their proper use: From now on they will be nothing but plastic means of expression and will no longer dominate in the work as they did in the past.

Neutral line, colour and form, in other words, elements that have the appearance of something familiar, are established as a means of general expression. As these means represent the highest degree of simplification, young people are the ones who must preserve them, determine their composition, and establish them according to their nature.

In order to approach the spiritual in art, we will make as little use as possible of reality, because reality is opposed to the spiritual. Hence, there is a logical explanation for elementary forms. As these forms are abstract, we find ourselves in the presence of an abstract art.

The universal can be expressed in pure manner only when the particular does not obstruct our path.

Sunday 29 November 2009

Sometimes the house will breathe for me, like an iron lung.

It happens at the panic point of some new poem,

often late at night or on a summer's evening when

the lines have grown asthmatic and the thought is numb

with fears of what the words might come to mean. It clunks

and grinds, immobilises - keeps my ebbing forms afloat.

Sometimes the house will be my ears, will listen like a bug

an agent planted long ago in these primeval hills

to eavesdrop sounds of alder, owl and adder, bat and badger, all

their worlds - more passing chatter than would keep surveillance teams

on song for years to come. It happens when the voices of

a poem drown the still small voice that gave it birth.

Sometimes the house speaks for (or to) me in an unknown tongue.

It tutts and putters like an outboard out at sea

and offers me the waves and rhythms it has found

among the deeper things that rarely come to be.

Easily mistaken for the muse herself,

it happens when I disregard her knowing words.

Sometimes the house imparts a kind of balance, like an inner ear,

tunes itself to keep in phase with thermals and horizons,

synchronizes movements with them in its posts and beams,

or eases its old bones against the cold. It shivers when

a poem's footings slide in shale - or when the lines strike out

to scale the heights, but then succumb to poesy's vertigo.

Thursday 26 November 2009

Sunday 22 November 2009

Poem as Screenplay : l

to forest scene

and sound of chainsaw,

thump of axe. Slow track

through undergrowth between

dense trees

towards the distant sounds

and to a clearing with a lumberjack.

He swings the final blow,

the redwood topples. Cut

to tree-top, looking down,

earth rushing up and... Cut to black.

Fade in to river scene and jam

of tree trunks piling up. Zoom in

to logs as wood made flesh and dressed

in finery of bark and twigs - Revealing

splash of camouflage! - and masks

of woodland things. [One face,

at least, to show, without disfigurement,

below the waterline - much like John Millais'

sad Ophelia.] Black boots

of military style come into shot,

prance lightly on and roll the human logs

and prod them with long poles

when they pile up, as now they do, in shot.

Pull back to show the owners of the boots:

militiamen with hand grenades,

machetes and Kalashnikovs. Quick

cutting here between men shown full-frontal,

firing, falling, falling into groups, then falling out,

and two-shots favouring in turn

the dying and the vanquisher - all played

the way that children play

"pretend" and make it up

at random as they go along.

The bodies drop and float between

the former logs (Not all the dead

are innocents!) still being rolled.

Fade out to black

Fade in to scene of river mouth with beach

and open sea beyond. Pan

to processions on the further bank,

where figures clothed in white are burying the dead

or placing mercenaries, draped in flags,

on funeral pyres. Close-up of log-cadavers

gently lowered into graves - stark contrast

to the way that they were felled. Slow mix

to view from bottom of a grave

a trunk descending slowly.

Sound of piercing screams, though slowly dying.

Slow mix to red with yellow disc intensely bright.

Cut to surf, then pan along the solar-heated beach,

past steaming rock pools, on to where

two funeral ships are burning fiercely just beyond

the shallows, and then on to where excited children

build their palaces and castles in the air -

or so it seems, with sugar candy spires

and leaning towers, their turrets born of dreams

and overflowing moats with drowning men.

Zoom in to read the tattoos on the children's backs:

"You can't blame life for death," says one,

"Death changes life - forever," says another,

"Is life or death the sucker?" asks a third,

and finally, more simply said, "My death it is that sucks!"

Fade out to grey to sounds of ululation.

Wednesday 18 November 2009

Why do I not love thee well, when I am nuts on yon?

Now I'll stick my neck out and suggest that you found the beautiful thingummyjigs much easier to come by. Further, I'll warrant that your characters for the ugly attribution are most likely to be works of art or architecture, and that your lovelies are natural objects or works of engineering. Of course, I'm on a hiding to nothing here, and your ugly customers could well be creatures of a nasty disposition or countenance or both, but then again, some of the nastiest are actually very beautiful - viruses, etc. And if I am wrong, I remain unrepentant.

No sooner had I posted my most recent effort on What is art? - The Blind Men and the Elephant than I decided to watch the first in the BBC 2's new Saturday evening series What is Beauty, which I had recorded. As I watched it began to occur to me that perhaps I should follow my art post with one on beauty, the two ideas being so intertwined. Almost synonymous, you might think. Even so, it might have got no further than the passing thought, had not two comment on the post suggested the same thing. And so I turned my thoughts more seriously towards such a post.

No sooner had I posted my most recent effort on What is art? - The Blind Men and the Elephant than I decided to watch the first in the BBC 2's new Saturday evening series What is Beauty, which I had recorded. As I watched it began to occur to me that perhaps I should follow my art post with one on beauty, the two ideas being so intertwined. Almost synonymous, you might think. Even so, it might have got no further than the passing thought, had not two comment on the post suggested the same thing. And so I turned my thoughts more seriously towards such a post.

And almost the first thing that occurred to me was how very much easier it was (for me) to think of very beautiful objects than very ugly ones. Maybe it is a reflection of how privileged we are in the West, for ugly things and awful environments certainly abound in the world, but I still think that, taking the world as a whole, they are probably outnumbered by those we might designate as beautiful. I do recall a conversation with my first boss (a fill-in job between school and college), a disagreement about Darwin and his Origin of the Species. He had given an example of something or other, and I thoughtlessly replied (something like) Ah, but you're talking about a very beautiful flower!.

He came straight back with And do you know of any ugly ones? A silly, rather trivial remark to have stuck in the memory for such a length of time, especially when I can no longer recall the rest of the argument, but stuck it has, and it seems to have coloured my thinking to some extent. To such an extent, in fact, that at times I'm not even sure that there is ugly.

There is frightening, disturbing, alien, unattractive, repulsive, hideous and many another, some of them terms which seem synonymous with ugly, but about ugly I remain unconvinced. Think of a slum scene, for example. We would unhesitatingly call it ugly, though it might well be that its repulsiveness derives from the horrors associated with it, rather than from a purely visual effect. I think how there was a time when all these adjectives would have been applied to somewhere like The Lake District. No one then saw beauty in woods and mountains, not until the Romantic poets and others saw it first. Before that, anything that smacked of wilderness was a dark place of great danger to be avoided at all costs. Everything about it was hideous in the extreme. Of course, all these concepts are subjective as are, for example, colour: your magenta, viridian and rose madder are probably nothing like mine, though we shall never know for sure.

So what is this thing we call beauty? Or would it perhaps be easier to turn our attention first to ugliness? I had thought to do so, but in a sense maybe ugliness is just an absence of beauty the way darkness is not an attribute in itself but an absence of light. Matthew Collins, the presenter of What is Beauty, detailed what he saw as different forms of beauty. He picked out the beauty of nature, of people (are they not part of nature?), light, spontaneity, the beauty of Contemporary Art galleries (an interesting theory of his own was that where once the exhibits in a gallery were beautiful and would special-up their environment, now they have no need of beauty and so all over the country the most stunningly beautiful galleries are being provided to special-up the works!) and others.

So what is this thing we call beauty? Or would it perhaps be easier to turn our attention first to ugliness? I had thought to do so, but in a sense maybe ugliness is just an absence of beauty the way darkness is not an attribute in itself but an absence of light. Matthew Collins, the presenter of What is Beauty, detailed what he saw as different forms of beauty. He picked out the beauty of nature, of people (are they not part of nature?), light, spontaneity, the beauty of Contemporary Art galleries (an interesting theory of his own was that where once the exhibits in a gallery were beautiful and would special-up their environment, now they have no need of beauty and so all over the country the most stunningly beautiful galleries are being provided to special-up the works!) and others.I think I see it more simply. First of all, it seems likely that beauty as we perceive it - all beauty - is an off-shoot of the sexual drive. As such it would have bestowed great evolutionary benefit by encouraging the passing on of good genes. The degree to which the emotions associated with the perception of beauty became applied, first to artefacts and symbols (most probably) and later to objects of other kinds would have been dependent on our developing intellect, as was - and is - the case with all the emotions. It is intellect that differentiates and decides which emotion is felt: a small man punches me and the emotion I feel is anger; a man bigger than me hits me and what I feel is fear. There is also a cultural element, of course.

It does seem that there are certain configurations of line that are perceived by our brains as inherently beautiful and others that have a negative charge. In my art school days a number of us were commissioned to paint some murals in a large mental hospital. One student produced a scene of boats on a beach. A psychiatrist came each day to check that there were no masts crossing the horizon - a configuration, he maintained, that would have had a negative effect on the mental stability of some of his patients. It is likely that other configurations, of shape, colour, proportion, texture and so forth, have their own contributions to make in one direction or the other.

It does seem that there are certain configurations of line that are perceived by our brains as inherently beautiful and others that have a negative charge. In my art school days a number of us were commissioned to paint some murals in a large mental hospital. One student produced a scene of boats on a beach. A psychiatrist came each day to check that there were no masts crossing the horizon - a configuration, he maintained, that would have had a negative effect on the mental stability of some of his patients. It is likely that other configurations, of shape, colour, proportion, texture and so forth, have their own contributions to make in one direction or the other.Beyond these there are attributes that are seen as inherently beautiful, symmetry being an important one. Again, a symmetrical face is often a pointer for good genes. (I would like to point out here that my markedly asymmetrical head is the exception that proves the rule.) Repetition - as in the reiterations of a fractal, in a simple repeating pattern or a texture - is another.

My apologies for leaving out details of the images. In order of appearance, they are:-

A Francis Bacon portrait.

The Rape by Magritte.

Two holiday snaps of Norway,

The Agony in the Garden by Giovanni Bellini

and a work by Odilon Redon.

Sunday 15 November 2009

The Blind Men and the Elephant.

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind

The First approached the Elephant,

And happening to fall

Against his broad and sturdy side,

At once began to bawl:

"God bless me! but the Elephant

Is very like a wall!"

The Second, feeling of the tusk,

Cried, "Ho! what have we here

So very round and smooth and sharp?

To me 'tis mighty clear

This wonder of an Elephant

Is very like a spear!"

The Third approached the animal,

And happening to take

The squirming trunk within his hands,

Thus boldly up and spake:

"I see," quoth he, "the Elephant

Is very like a snake!"

The Fourth reached out an eager hand,

And felt about the knee.

"What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain," quoth he;

" 'Tis clear enough the Elephant

Is very like a tree!"

Is art, do you think, like love: something that we recognise for what it is when we run into it, but deucedly hard to define? Or is it more like religion: we know, within limits, what it is, and what it is supposed to do, but not where it comes from - except that it has something to do with the very oldest part of our brain and its now long-forgotten, mystic past?

I ask the questions after reading an article by Richard Eyre in which he addresses these questions. Or to speak more accurately, he recently gave a speech at the opening of a new theatre at The Cheltenham Ladies College, an edited version of which was published in The Independent. Understandably, the first half of his speech - or at least, the edited version of it - was devoted to the theatre and was in large part autobiographical. But then he weighed in with: Why do we need theatre? In fact, why do we need the arts? and a little later: But what do we mean by "art"? A simple enough question, one which we perhaps should ask ourselves with some regularity. He then proceeded to outline his definition and began to carry me along with him, mentally nodding in assent at the points he was raising.

I ask the questions after reading an article by Richard Eyre in which he addresses these questions. Or to speak more accurately, he recently gave a speech at the opening of a new theatre at The Cheltenham Ladies College, an edited version of which was published in The Independent. Understandably, the first half of his speech - or at least, the edited version of it - was devoted to the theatre and was in large part autobiographical. But then he weighed in with: Why do we need theatre? In fact, why do we need the arts? and a little later: But what do we mean by "art"? A simple enough question, one which we perhaps should ask ourselves with some regularity. He then proceeded to outline his definition and began to carry me along with him, mentally nodding in assent at the points he was raising. First of all, though, what it is like: passionate, complex, mysterious, thrilling; and then what it does: tells us the truth about ourselves, helps us to fit the disparate pieces of the world together, helps us to try to make form out of chaos; and then, finally, what it must and must not be: has to be ambitious, not satisfied with wanting to please, has to struggle against mediocrity, aspire to be excellent, must have form, there has to be complexity, there must be mystery, must be serious, can't be trivial,there has to be an element of pleasure, of sensual enjoyment (though, unusually, there was no actual mention of beauty), there has to be a moral sense...

Nothing there to disagree with, but as I read on, I found my mental nods turning to frowns of concern. I was reading some sort of creed, it was becoming too prescriptive. Now, I'm adding a can't of my own: for me, art cannot be prescriptive. But I still had a problem: I agreed with the individual points he was making (mostly), but not in the context in which he was making them. Not in answer to the question What is art? For me, he was answering some other question. He seemed more on the right track, though, when he began to speak of art as something that gives form to life and to the world in which we live. And then again when he credited it with the ability to give the world and its threats and bullying ways a human scale. So much in politics, technology, science and human relationships is mega these days, and seemingly beyond our emotional resources to tackle. Art can step in at that point. By its fruits shall you know it. But art is a very complex elephant indeed, with many trunks and tusks and tails etc, and it is his use of the imperative that worries me. Too many musts. If he had said art must be or do at least one of these... but the implication was that it had to be comprehensive.

And then somewhere into my thinking there floated the matter of Sir Andrew Motion and his poem An Equal Voice, written and published (in The Guardian) as a tribute to the war veterans for Armistice Day. The poem was well received until Ben Shephard, who had spent ten years collecting the reminiscences of veterans for his book A War of Nerves accused Motion of plagiarism, of having lifted 17 passages from his book and stitched them together to produce his poem.

The following were given as an example:-

First, this from A War of Nerves:

"War from behind the lines is a dizzying jumble. Revolving chairs, stuffy offices, dry as dust reports..."

"marching men with grimy faces and shining eyes..."

"bloody clothes and leggings lying outside the door of a field hospital..."

"I have been in the front line so long, seen many things..."

Then this from Andrew Motion's An Equal Voice:

"War from behind the lines is a dizzy jumble. Revolving chairs, stuffy offices, dry as dust reports..."

"marching men with sweat-stained faces and shining eyes..."

"bloody clothes and leggings outside the canvas door of a field hospital..."

"I have been away too long and seen too many things..."

Andrew Motion's reply was that "all real artists are magpies". Be that as it may, it did open up in my mind the whole question of found art and how it is reconciled with whatever definition, explicit or implicit, you have for the act of art-making and its outcomes. Of course, we could say the same for any one of scores, perhaps hundreds, of art's various genres. If, with Richard Eyre, you believe that art to be art must demonstrate a mastery of some supreme skill, then you may have to rule out found art. Unless you are prepared to argue that the ability to see a poem in, say, a passage of prose, is sufficient skill in itself.

There is, I believe, nothing to beat going back to basics at such times, and for me basics often means child art or primitive art. I don't believe I have ever met a child who was worried about what art was for. The purpose of pretty much every other man-made thing in the universe worries them - but not art. So I go back to Raymond. I do believe I have blogged about Raymond before - though I may have called him by a different name. Raymond, though, was his name.. Raymond was eight years old, or thereabouts, backward (illiterate), but bright. He was in what these days we would call the Special Needs class, but was then known as the Remedial class. I was a brand new teacher fresh out of college, the last person on the staff who should have been given that group (because the least experienced), but the only one to volunteer. By such considerations are the fates of the innocent decided. It was a Friday morning (I think!) and our first lesson was science. I had to introduce them to the latest theory about how the universe came into being - not what you're thinking, for back then it was Continuous Creation. (A pupil once asked me if I was alive in the Stone Age. More than that: I go back to before The Big Bang!) The lesson concluded and it was time to troop into the hall for assembly. There the head gave us all the Creation of the world from The Book of Genesis. Raymond was becoming distressed. Following on from assembly we had a short choosing period. Raymond asked if he could have two large sheets of drawing paper. I agreed. He taped them together, then turned them over and began to paint. He didn't have long, didn't need long. Very soon he had a fantastic landscape covering the sheets. There were mountains, rivers, a valley, trees, a sun in the sky, stars - and two moons. In the valley were two figures, a small figure pointing up at one of the moons and a large figure looming over him and with his arm stretched out towards him, palm uppermost. His distress was evaporating markedly as he worked.

Tell me about it, I said. The little man, I was told, was Adam. He was pointing at one of the moons. (The Russians had, only a day or two before, launched their first Sputnik.) Adam was saying to God: See, I put that one up there! So I asked him what God had to say to that and was told: He said, "And I just made this little spider. Now beat that!" The consensus of opinion on the staff and elsewhere was that the dialogue could not have been Raymond's own. He had probably heard it somewhere. At home, maybe. Or at church. He'd picked it up somewhere. Yes, he probably had, but in my book he had processed it and made it his own. Yes, all true artists are magpies, but it's what you do with the stolen milk bottle tops that counts - and that may depend on why you stole them in the first place.

Have I answered the question? Have I defined what is art? No, I don't believe I have - and I'm not sure that I could, not to my own satisfaction. I have simply given an example of what I believe to have been a piece of art by anyone's standard, adult or child.

Thursday 12 November 2009

The Glass Room

When Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall won this year's Booker Prize, by all accounts so convincingly and deservedly (for I have not yet read it, though I am about to put that right), there arose a persistent rumour that the judges had unofficially placed Simon Mawer's Glass Room in second place. It caused some commentators to raise again the question of whether it wouldn't be better in future to split the prize money in to three and award first, second and third prizes. (And interestingly enough, I was reading only a couple of days ago that the French equivalent to our Booker awards the winner a cheque for a measly ten euro. The award is no less coveted, it seems.)

When Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall won this year's Booker Prize, by all accounts so convincingly and deservedly (for I have not yet read it, though I am about to put that right), there arose a persistent rumour that the judges had unofficially placed Simon Mawer's Glass Room in second place. It caused some commentators to raise again the question of whether it wouldn't be better in future to split the prize money in to three and award first, second and third prizes. (And interestingly enough, I was reading only a couple of days ago that the French equivalent to our Booker awards the winner a cheque for a measly ten euro. The award is no less coveted, it seems.)It so happens that I had The Glass Room in my to read pile and took it with me recently for my holiday reading. It's a cliche I know, but I genuinely could not put it down - not for long at any rate.

The focus for the story is pre-war Czechoslovakia, though it begins in Venice where Liesel and Viktor Landauer (of Landauer car fame and wealth) are on honeymoon and where they meet and become friendly with a stranger by the name of von Abt, who proves to be an internationally regarded architect. Viktor suggests that von Abt might like to design a house for them. The suggestion excites von Abt and both men become enthused by his idea of a house of the future. "Ever since man came out of the cave he has been building caves around him, he cried. Building caves! But I wish to take man out of the cave and float him in the air. I wish to give him a glass space to inhabit."

Glass space, Glassraum. It was the first time Liesel had heard the expression..

As you might have guessed, the house becomes the hub of the story. There was such a house, though how much of the story is based upon the people and events associated with it, is difficult to guess. In the story the house becomes a metaphor, indeed a series of shifting metaphors. At first it stands for the optimism with which the story's three main protagonists regard the future. The two men particularly, have no doubt that the new style of house will breed a new way of thinking and living. The house will prove to be Abt's great masterpiece with travertine floors and an internal wall of onyx in a room composed entirely of glass. In such a house the way a man thinks and lives will become more open and transparent, more honest, more worthy.

By the time the plans arrive Liesel is pregnant. Viktor explains them to his wife: "He wants to build a steel frame. Apparently there will be no load-bearing walls at all, just the whole thing hung on a steel frame. And where the uprights pass through the interior he is proposing to clad them in chrome. Gladzsend, he calls it. Shining. Hard steel rendered as translucent as water." Viktor pulls a letter from his pocket and reads: "Steel will be as translucent as water. Light will be as solid as walls and walls as transparent as air." But before the baby is born Viktor is having an affair with a woman called Kata whom he met by chance in a park, she asking him for a light.

So where does that leave the great metaphor which is the house? There is irony now in talk of honesty, transparency and openness. Over the course of the story the house will become a metaphor for other concepts (tranquility, illusion, dream), for these are the dark days before W.W.II, and although Liesel is Aryan, Viktor is Jewish and they have to flee, leaving the house which has come to mean so much to them. Before that moment arrives however, the pressure of external events causes Kata to be taken on to look after the young child, much against the wishes of Viktor who has considerable anxieties about the move. However, Viktor arranging papers for her to allow her to accompany them, initially to Switzerland. Sadly, she does not make it across the border.

There follows a confused period in which the house is first confiscated and then changes hands and purpose several times. For a while the Nazis have it for their own particular brand of research - into racial characteristics. It becomes a clinic and a refuge for handicapped children. Viktor's one time chauffeur becomes a self-appointed janitor with eyes on the black market. Then comes the cold war and, eventually, the collapse of Communism clearing the way for the return of the family - but a very changed family. Doctor Tomas, who had run the clinic, had had a firm belief that the past is an illusion. He had also shared (unofficially) the glass room with a girl called Zdenka, letting her hold her dance classes there, in return for which she would dance for him, and for him alone, each evening. Tomas had found it very disturbing that the Glass Room possessed a past, that it had not always been this sterile gymnasium, this fish tank in which Zdenka danced for him, this room of glass and quiet." Dr Tomas had maintained that there is no such thing as time. Past and future are both illusions. There is only a continuous present.

The author includes an Afterword, which for me threw further light on the metaphor and on his thinking, though I think I would have preferred to read it first. I am therefore including it, almost entire. He writes:-

The title of this book, The Glass Room, needs some explanation.It is, as is clear, a translation of the original German - Der Glasraum. Raum is, of course, "room". Yet this is not the room of English, the Zimmer of our holidays, with double bed, wardrobe and writing desk beneath a print of some precipitous Alpine valley. Within the confines of the Germanic "room" there is room for so much more. Raum is an expansive word. It is spacious, vague, precise, conceptual, literal, all those things. From the capacity of the coffee cup in one's hand, to the room one is sitting in to sip from it, to the district of the city in which the cafe itself stands, to the very void above our heads, outer space, der Weltraum. There is room to move in raum.

So: The Glass Space, perhaps; or The Glass Volume; or The Glass Zone. whichever way you please. Poetry is what is lost in translation, as Robert Frost so memorably said. So we do our best with this sorry and thankless task, aware that we will be condemned for trying and condemned for not trying. Take it as you please: The Glass Room; der Glasraum.

So have I any quibbles, regrets, carping comments? Well, certainly nothing that is more than nit-picking. There was not much in the way of character development that I could see, and that is something I look for in a novel, but it is something for which this particular story offers very little in the way of opportunity. People disappear for years and come back changed, it is true, but the change occurs off stage, not in front of the reader. There is, though, one exception: you might say that the house, der Glasraum, is the chief protagonist, and we do watch its character change and develop considerably.

Monday 9 November 2009

Haiku (somewhat calmer) moments from the deep.

but in the on-board swimming pool,

a giant tsunami.

From the sea, the sun's glare.

The wake of an inflatable

drives shards of darkness to its heart.

Small tugs nudge a massive vessel

into leaving its safe haven

for the open sea.

Thick smoke to starboard...

as if the crew had need

to simulate disaster!

Night orchard now, the sea's

white blossoms brush the windows.

Unseen branches jar the glass.

White horses crest the waves.

Behind them, riderless,

dark troughs for chariots.

Inclement weather.

Lifeboat drill is held indoors.

Boat 2 is in the lounge.

A midnight roll.

My tumbler and its contents

have joined me in the bed.

Another swell, but this one

merely shifts the distribution

of my weight from shoe to shoe.

In mimicry of pilot fish

gulls' shadows swim before

dark porpoise-shapes.

Deafening, the noise

a cable makes. For sure

an anchor chain could make no more.

Friday 6 November 2009

Memorable

And so finally we left the house to the tender mercies of the decorators, electricians and others, to make our way to Southampton, to the Saga Ruby. We had cruised before , but on her sister ship, the Saga Rose. Two very rough days in the channel and across the Bay of Biscay left us wondering what perversity in our natures had led us to choose to cross Biscay at the end of October. (A word of advise: don't.) On the second day we ordered toast and coffee from room service. The ship decided at that point to do a double skip sideways. The tray sailed through the air and crashed to the floor. It gave a whole new meaning to the phrase half a cup of coffee. Not one piece of crockery escaped. The wind by then was gale force 8/9.

As if to compensate us for the rigours of those two days, The Mediterranean gave us ten glorious days of sunshine and cloudless skies, at times a little too hot.

At Cadiz we were taken to a winery and treated to a display of genuine Flamenco Dancing. The dancing was breathtaking. Partly, no doubt, because we were inches from the stage and had just finished the first tasting. I took numerous photographs - you can imaging - which no doubt would not have been technically brilliant, though far superior to those I took after the second tasting. Unfortunately, the memory card developed a fault (nothing to do with the tasting, I assure you!) and I have been unable to access them. Does any good soul out there know of a method to retrieve such images?

The sting was in the tail, though: returning across Biscay, the wind a mere force 7, but the sea feeling much rougher than the previous 8/9, Doreen was quite ill and had to spend all of Tuesday in bed. The final (nearly!) "highlight" came at 4 am when we were hit by a huge wave (shades of Hokusai!) which lifted the bows of the ship (where, as it so happened, yours truly was sleeping), stopping it dead in its tracks and doing - we were told - a great deal of damage around the ship. Not, though, to yours truly, the worst that happened to us was that a larg(ish) and very heavy safe mounted just below eye-level in one of the wardrobes crashed through the doors of said wardrobe and landed upside down inches from the foot of my bed - and feet, of course! It quite woke me up.

Other highlights were meeting up with the Saga Rose on its last journey and a day of celebrations beginning with a church service, led by Lord Carey, former Archbishop of Canterbury, and culminating in a spectacular firework display.

We made it home on Wednesday. The workmen had long gone, the boxes and the innumerable layers of dust were undisturbed. For the most part they remain so. I still feel like a monk, but now in a cardboard cell.

Of course there were others, not least the gastronomic delights, the chef's ice sculptures (shown in accompanying photographs - no more than snaps, really)and the various ports of call.

What a lovely homecoming, though, to discover that so many of you had thought it worthwhile to comment in my absence. So far beyond my expectations, that. Thank you all so much. I have posted replies, though not as personal as I would wish, time being at a premium at present with all these boxes now to unpack and much to be done before I can access my books.

Tuesday 3 November 2009

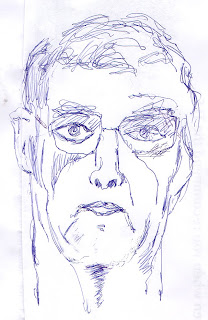

Blind Trace

Back in February I re-posted a much older write-up of an exhibition I had seen of the later work of Victor Pasmore. My post was called With Eyes Tight Shut, for the images exhibited were a selection of those seen and painted by Pasmore with his eyes closed. I had known Pasmore's work many years before when he had been a very different painter and I was immensely impressed with these later works.

Back in February I re-posted a much older write-up of an exhibition I had seen of the later work of Victor Pasmore. My post was called With Eyes Tight Shut, for the images exhibited were a selection of those seen and painted by Pasmore with his eyes closed. I had known Pasmore's work many years before when he had been a very different painter and I was immensely impressed with these later works.Maybe ten years or so before that I had developed a tremor of the arms. It is nothing nasty, a genetic thing which my father suffered from and which has begun to show itself in my brother. It was and is more nuisance than sinister. Among other inconveniences it greatly interferes with my ability to draw. After seeing the Pasmore exhibition I experimented for a while with drawings and paintings of the images that appear when I close my eyes, and I blogged about this for I was interested in comparing my own experiences with those of others. Not surprisingly perhaps, I found that there seemed to be very little conformity in the images, each person's images were as individual to them as their dreams. At the same time I flirted with a way of drawing that I had heard about in my student days, but not tried, a method that involves not looking. But other issues overtook me and I did not pursue either interest for long. Recently, I decide to try this method of drawing. It was not a serious attempt. I tried it out on a scrap of paper just before going to bed - a quiet time when I would normally have been reading or maybe watching a T.V. program I had recorded.

Then came one of those synchronicity thingies when The Guardian newspaper, produced a booklet on How to Draw which was given away with the Saturday edition of the paper. I almost did not look at it, assuming that it would consist of those cringe-making formulas for drawing horses, trees, flowers etc. A this-is-how-you-do-it treatise. Fortunately though, I did look at it - and it wasn't that at all. In fact, there was a small feast of excellent articles by established artists (innovative art tutors the book called them) and students telling - amongst other things - how they go about their drawin gs and why they do it that particular way. And yes, among these was the draw-but-don't-look idea. Indeed, there were several versions of it.

One thought I had nursed when experimenting with this was that maybe it would give my drawings a bit more life and freedom of line. It didn't - or maybe I should say that it hasn't yet, for it is early days. What it did do, though, incredibly, was circumvent the tremor. The drawings made by this method show no sign of the shaky hand syndrome that has become so noticeable in my drawings generally, to such an extent that I had almost stopped making them. This took on added interest when I read that when Chenai - one of the model students - tried out the technique his hand became exceedingly shaky. He did, though, insist that you should hold the pencil out at arm's length to draw, which I have not done.

The method, then, is simply this: that you do not look at the paper on which you are making your marks. You look continually at the subject and nothing else. I have now modified that slightly but importantly - for me, at any rate, it has proved important. I do not look at the drawing whilst I am making a mark. I will look occasionally to reposition the pen or pencil. So for example, having just finished drawing the right eye I will look at the paper for the purpose of transferring the pen to the other eye, but then look away before beginning to draw. An alternative aid I have introduced is that when beginning, say, an ear, I may use a finger of the non-drawing hand to mark the start point, so that I can return to it if need be.

The self portrait shown here is my first two attempt using the method. I used the method in its pure form - no looking whatsoever. It is rather crude, to say the least. There is none of the liveliness of line I had been hoping for, and the shape of the head is not correct, which indicates to me that my body image is not what it was - not surprisingly perhaps, for the body image is yet one more thing that deteriorates with age. (In this connection, what I mean by body image is the awareness of the position of the individual body parts in space and their relationship to each other. Can you, for example, touch finger tips behind your back at the first attempt?) So, is not a good likeness and it is not good from a drawing point of view, as a piece of art. Nevertheless, it is, as I say, early days, and I do think the method has possibilities.

Wednesday 28 October 2009

Hopper's America

He felt the weight of prairie vastness in the urban space,

the loneliness such sparseness of expanse can bring,

the seep of grassland into city wariness, the way

great distance can be squeezed into a downtown street.

He saw the spaces infiltrating neighbourhoods

like wedges prising could-be friends apart, or solid hedges,

impenetrable, keeping people in. For hedge, a block

of darkened pigment: loneliness, a figure gaoled in light.

His landscape was a tableau frozen from time's stream,

a known world, stranger than we'd known, where nothing moved.

There were no doors, no corridors, no exits from the bleakness

and no absconding from his silent dream. No recoil to reality.

Always, it seemed, an unknown ghost was waiting to appear.

Friday 23 October 2009

If I had never read Heaney...

He appeared on the hill at first light. The scarp was dark against a greening sky and there was the bump of the barrow and then the figure, and it shocked. I thought perhaps the warrior buried there had stood up again to haunt us. I thought this as I blew out the lanterns one by one around the pen. The sheep jostled and I was glad of their bells.

He appeared on the hill at first light. The scarp was dark against a greening sky and there was the bump of the barrow and then the figure, and it shocked. I thought perhaps the warrior buried there had stood up again to haunt us. I thought this as I blew out the lanterns one by one around the pen. The sheep jostled and I was glad of their bells.